For reservations to experience “nkwiluntàmën: I long for it; I am lonesome for it (such as the sound of a drum)” by Indigenous artist Nathan Young, please go to https://nkwiluntamen.com/

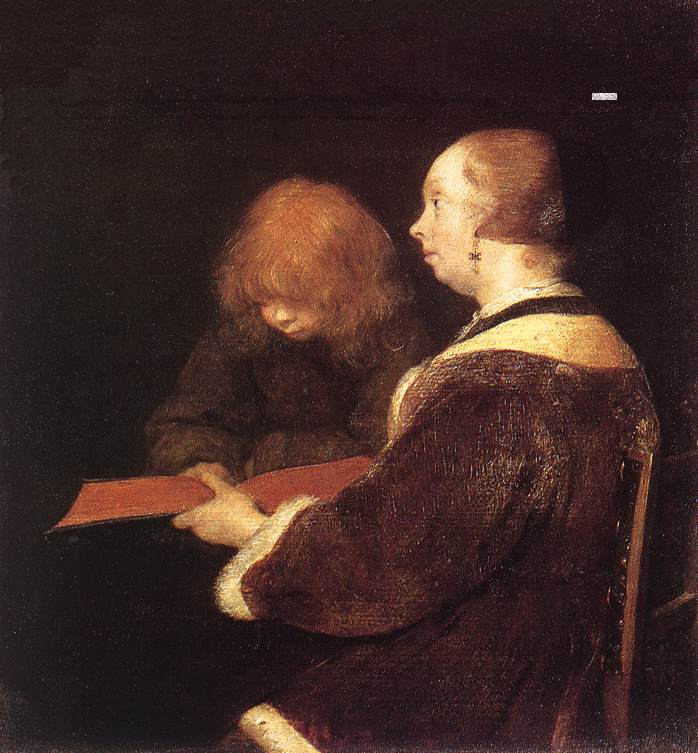

Learning Your ABC’s and 123’s – A 17th-Century Education

- August 27, 2012

- Posted By: Pennsbury Manor

“Education is the stamp Parents give their Children”

– William Pen

When we think of standards in education today, it is safe to say it has come a long way since our colonial forbearers. We talked last month about the realities of colonial childhood, particularly for Quakers. Because of their responsibilites to their family, general education in the 17th century was erratic.

Without buildings dedicated for teaching, communities had to organize financing for the construction of school houses, funding teachers’ salaries, and getting parents to agree to let their children spend the day in a schoolroom instead of helping at home. This last condition was sometimes impossible for poorer families, who needed their children’s help to survive.

As a result, families often chose to become their own center of education. So if a child was to learn to read, write, or calculate, someone in the family had to teach them. This also meant time away from chores, but these skills would be necessary if a son (especially the one to receive the family inheritance) were to manage the family’s business and participate in public affairs.

The common way for the children to learn to read and spell was through the use of a hornbook. Named literally for the materials that made it, a hornbook was a thin piece of wood backing topped by a piece of printed, then covered with a layer of horn. The horn was thin enough to let the paper be seen for reading, and all was held together by strips of metal around the edges. The book had a small handle with a hole for string so the book could be carried, either around the neck or over the shoulder. The printed page would include an alphabet with large and small letters, along with simple syllables and the Lord’s Prayer. The backs of the books were often decorated with a design. Used nearly every day, they were often used until worn out, meaning few 17th-century hornbooks exist today.

Quakers used the hornbook and some of the other practices of traditional 17th-century education; however, the main ideas behind their educational practices were based in their religious beliefs. They tried to control the children’s environment, preserving their faith and promoting certain behaviors including dress, speech, and silence. This led Quakers to believe that education was a foundational tool for spreading their practices, and opened their own institutions separate from the Protestant or Angelican schools.

Because of their isolation and irregular practices, Quaker education did not prepare children (mainly boys) for college. Classic topics (Latin and Greek) were often not included in their education. Moreover, Quakers were also “free in their criticisms of traditional schools.” Even Penn noted the issues with English schools, saying “We are in Pain to make them Scholars, but not Men! To talk, rather than know.” Nonetheless, both Penn and other Friends wanted “classical learning with the study of useful knowledge”. This practical knowledge meant being able to” read, write, and cipher” while gaining “a fuller appreciation of the Creator”. William Penn also made his sentiments on education known through letters to his wife, which can be viewed in a previous post entitled, Stay in School.

Classical and practical education also came in the form of apprenticeships. Apprenticeships were seen as privileges that provided an education which ensured a child’s livelihood later on. On the other hand, becoming an apprentice could be a traumatic experience, seeing as many children (again, boys) would start young (usually around 12 years old) and leave their families to live with their master. This strict frame for growing up was backed by the Proverb 22:6, a popular verse amongst Friends: “Train up a Child in the way he should go, and when he is Old he will not depart from it.”

Realistically though, we know better than to think all children listen to their parents! For Penn this proved true and it’s safe to say that his children didn’t quite follow his religious and education views through and through.

Mary Barbagallo, Intern

Sources:

Child Life in Colonial Days, Alice Morse Earle,Corner House Publishers, 1989, Williamstown, MA.

Everyday Life in Early America, David Freeman Hawke, Harper and Row, Publishers, Inc. 1988, New York, NY.

The Quaker Family in Colonial America, J. William Frost, St. Martin’s Press, Inc. 1973, New York, NY.