This post was written by Steve Samuel, a new volunteer interpreter in the Pennsbury Manor Joyner’s Shop! He thought many people, like himself, wouldn’t know the difference between a Joyner and all the other woodworking trades, so he did some research…

THE WOODWORKING TRADES

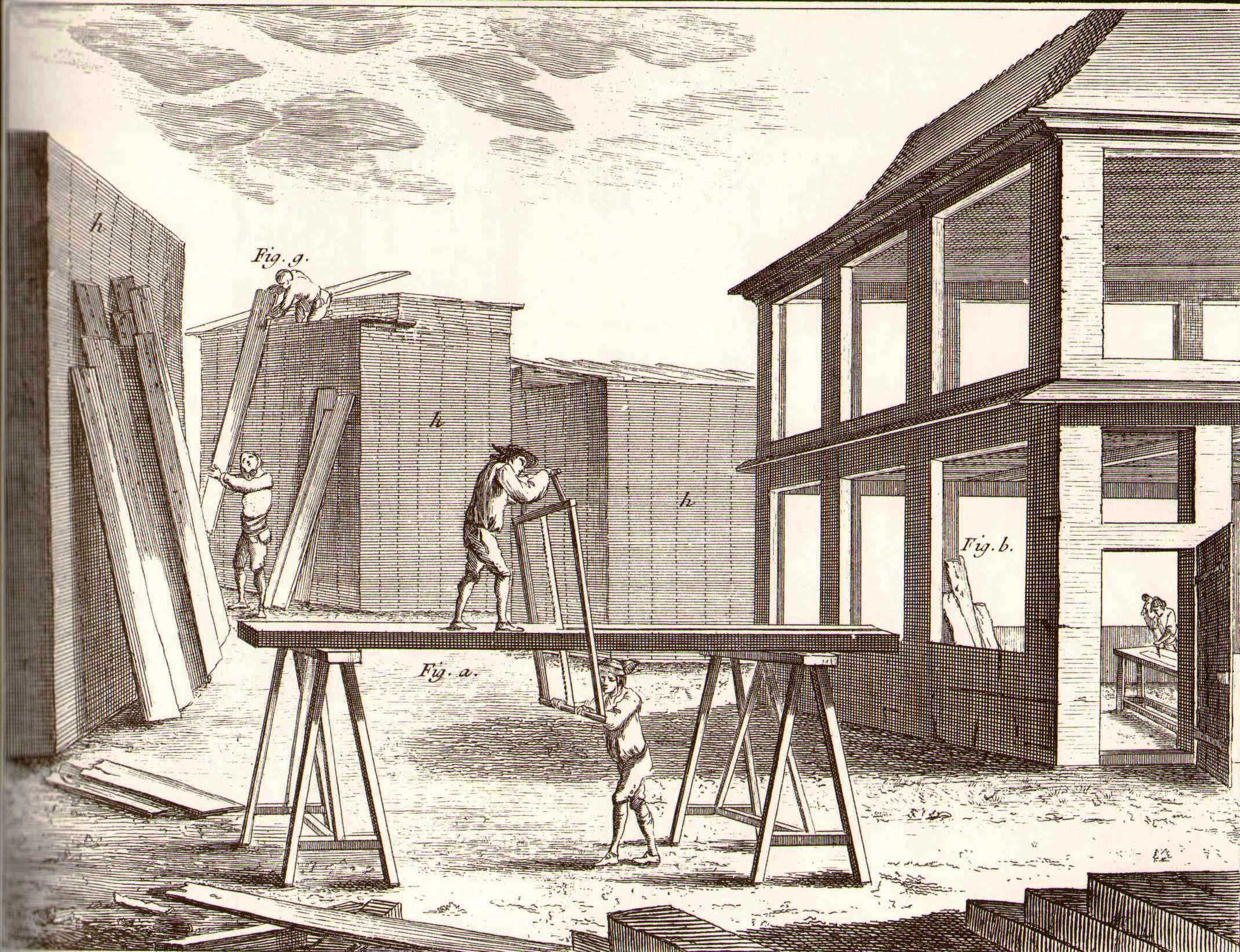

During Manor tours, it is not unusual for visitors as well as the occasional tour guide to stand in front of the Joyner’s Shop, and refer to the joyners as “carpenters”. Historically, however, professional joyners distinguished themselves from carpenters as matters of both business and pride.

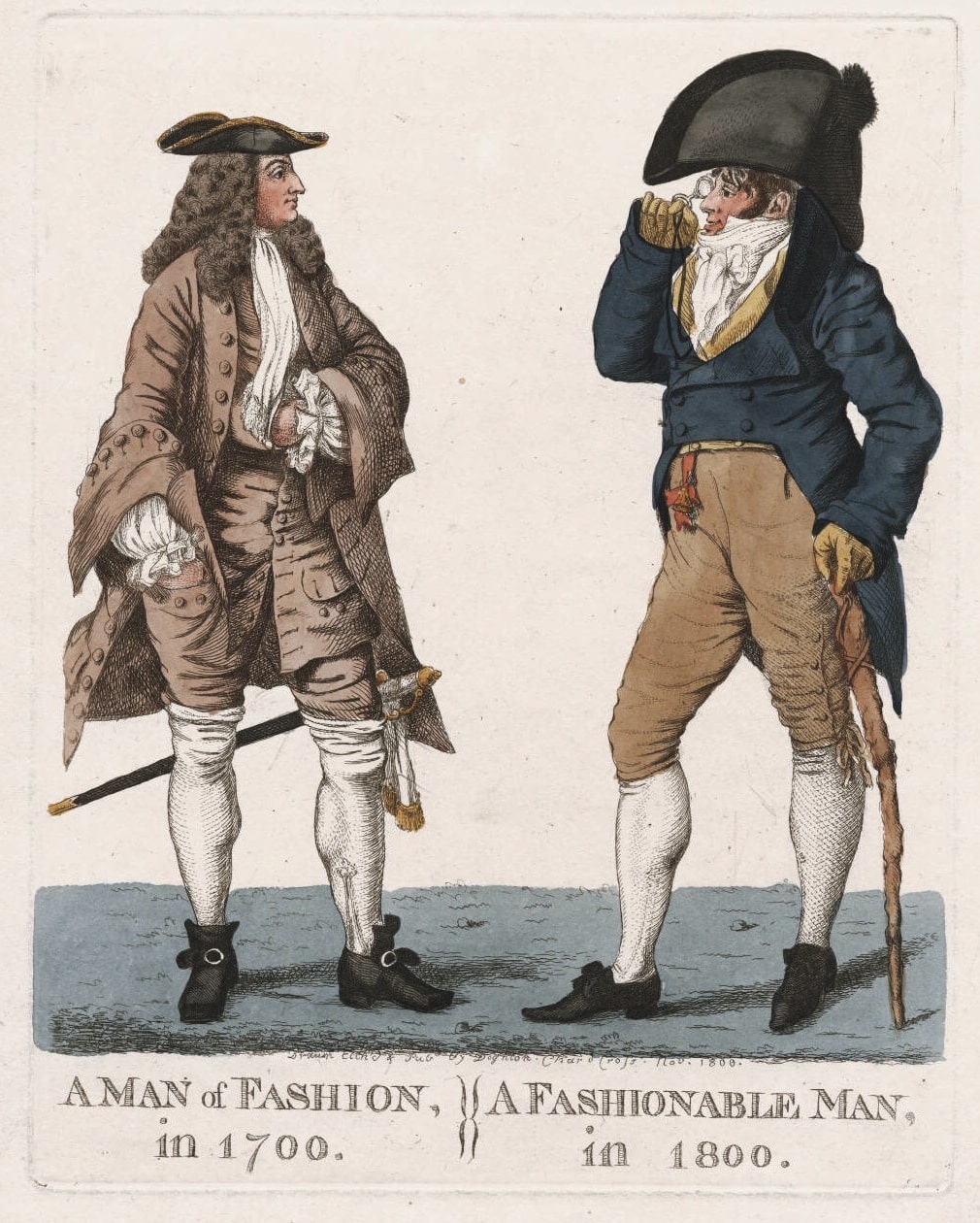

Dating to the mid-1400s, furniture making was overseen by the Guild of Master Carpenters, who subcontracted work to joyners, inlayers, turners, etc. These specialists began forming their own companies (guilds) in the 16th and 17th centuries. Each specified its distinct form of woodworking to make sure that others were not infringing on their trades. They defined who could practice the trade, and who could not, not unlike our present-day labor unions. In 1563, the Great Statute of Artificers established that the apprenticeship for a joyner would be 7 years. The Faculty of Joyners and Ceilers or Carvers of London” received its charter in 1570. Members were expected to adhere to regulations and quality standards, and could be fined for substandard work.

In general, carpenters were mainly responsible for structural work. They also made nailed, or “boarded” furniture. They tended to work on-site. Joyners, in contrast, joined pieces of wood together, using the mortise and tenon joint as the basis for construction of furniture, wainscoting and other fixed woodwork and paneling. Much of the joyner’s work was performed in his shop, alone or with 1-2 apprentices. In England and the early American colonies, the joyners were the true craftsmen of household furniture.

Come by Pennsbury Manor next Sunday, May 6 from 1:00-4:00 to see our Joyners working in their shop. Blacksmithing and Sheep-Shearing will also be happening around the site.

For Further Reading:

Chinnery, Victor Oak Furniture, The British Tradition (1979)

Fitzgerald, Oscar Four Centuries of American Furniture (1995)

Humphrey, Nick Furniture and woodwork in Tudor England: native practices, methods, materials and context Furniture, Textiles and Fashion Department, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

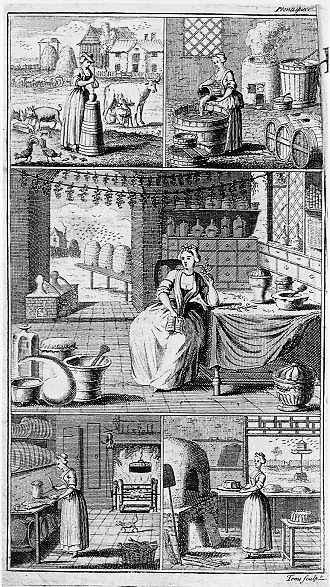

Those of you that have walked the grounds of Pennsbury may have seen a building called The Worker’s Cottage. This reconstructed outbuilding’s original purpose or even existence is unknown, but we use it to talk about the laboring class’s lifestyle in early colonial Pennsylvania. Most people did not live as luxuriously as William Penn’s family. Most homeowners, or people who worked as an apprentice or slave for a homeowner, lived in a 1-2 room house similar to this.

Those of you that have walked the grounds of Pennsbury may have seen a building called The Worker’s Cottage. This reconstructed outbuilding’s original purpose or even existence is unknown, but we use it to talk about the laboring class’s lifestyle in early colonial Pennsylvania. Most people did not live as luxuriously as William Penn’s family. Most homeowners, or people who worked as an apprentice or slave for a homeowner, lived in a 1-2 room house similar to this.