Pennsbury Manor’s interns have been hard at work researching new stories for our 75th anniversary. As they continue to explore Pennsbury’s history, we’ll be sharing their reflections on what they’re discovering!

Over the past two months, I have been searching through the archives of Pennsbury Manor. My mission is to find points of interest that would help me in my proposal for a 75th anniversary exhibit. I must admit, the first time I looked through the archives I was overwhelmed. There were so many papers, maps, charts, and photos to look through that at times I have felt like I was going to drown with information!

But I have discovered some gems, and one of these gems is the Barge. A reproduction based on Penn’s original description, it’s currently located in an open shed right outside the Visitor Center. I noticed in following tours of the site, the barge was often glossed over, and I found myself doing the same in my own tours. So I decided to focus much of my research on this fascinating boat.

What I found really surprised me. The barge, which was completed in 1968, spent much of the late 70s and early 80s touring various museums and historical site as an important interpretation symbol of 17th century transportation. People even had the chance to use the boat in the water. I found dozens of documents detailing requests from other institutions such as the American Maritime Museum requesting the barge for various events. There was even a year (1988) where the barge took a month long journey across the Delaware River (for community events) with an additional trip to Erie.

One of the most interesting items I found was a Youtube video featuring the barge from a mini-series in 1986 called George Washington II: The Forging of a Nation. Check out the video at this link and look for the barge to appear around the 7:29 mark: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fhkY25xfH9g

Unfortunately, all this travel took a toll on the barge, and by the early 90s it was time to either retire the barge or face the cost of major repairs. It just amazed and saddened me how the incredible journey of this object has gotten lost over the years. What I’m working on now is to answer how it came to be this way, and could anything had been done differently?

By Lindsay Jordan, Intern

Do you have memories of seeing the barge in action? Please share in the comments!

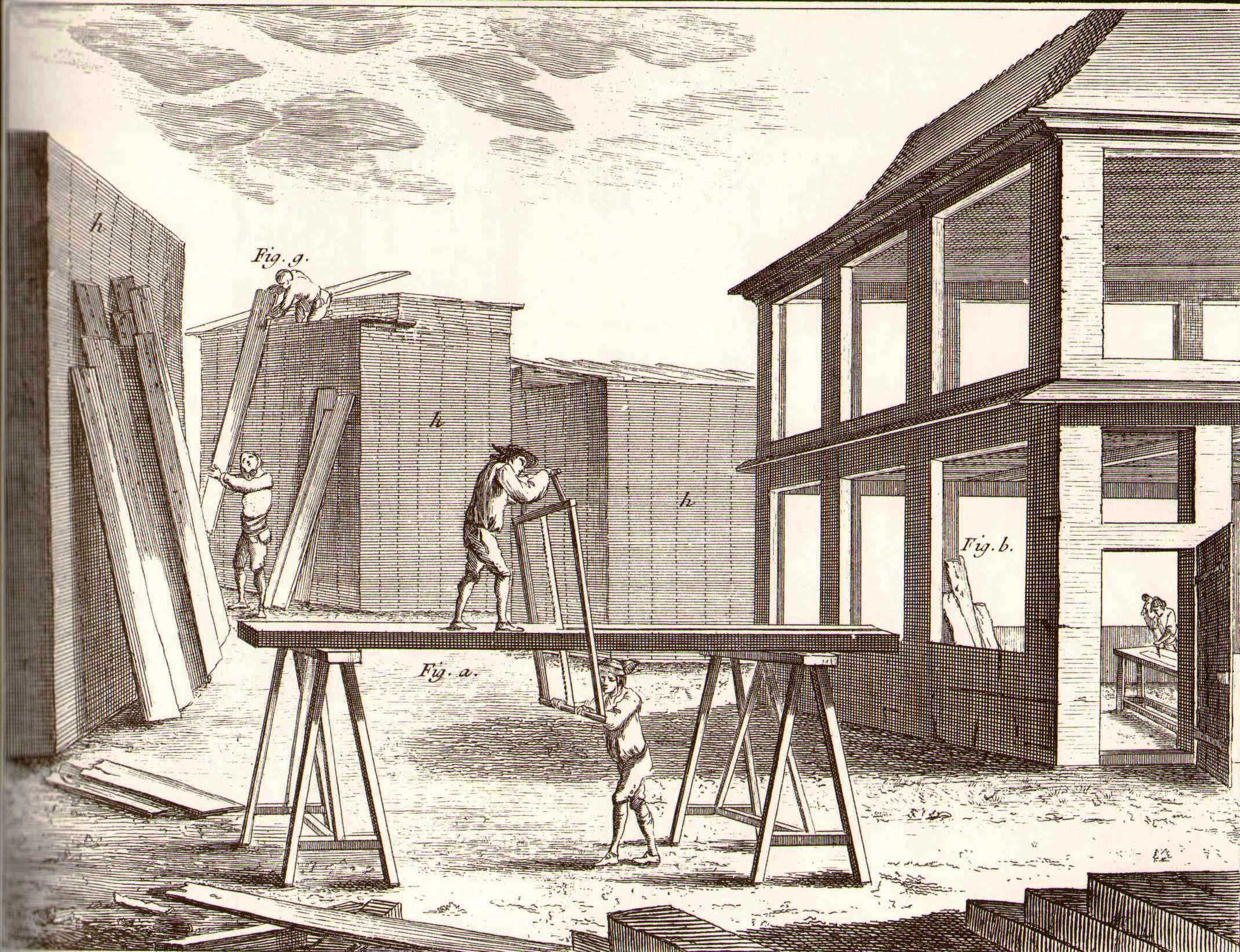

Those of you that have walked the grounds of Pennsbury may have seen a building called The Worker’s Cottage. This reconstructed outbuilding’s original purpose or even existence is unknown, but we use it to talk about the laboring class’s lifestyle in early colonial Pennsylvania. Most people did not live as luxuriously as William Penn’s family. Most homeowners, or people who worked as an apprentice or slave for a homeowner, lived in a 1-2 room house similar to this.

Those of you that have walked the grounds of Pennsbury may have seen a building called The Worker’s Cottage. This reconstructed outbuilding’s original purpose or even existence is unknown, but we use it to talk about the laboring class’s lifestyle in early colonial Pennsylvania. Most people did not live as luxuriously as William Penn’s family. Most homeowners, or people who worked as an apprentice or slave for a homeowner, lived in a 1-2 room house similar to this.