As the school year quickly shifts into high-gear and stores advertise their latest sales on backpacks and sneakers, the staff at Pennsbury can’t help but notice the differences between modern life and childhood back in the 17th Century. We spent the summer posting on children’s daily lives and education, so maybe it’s time to feature what they’d be wearing!

“Dress to impress” is surely a phrase we’re common with this day in age, but not something you would necessarily abide by in William Penn’s time. In 17th-century England and the colonies thereof, clothing was expensive. With the majority of the common folk working solely to survive, the average household could not afford to pay as much attention to fashion as their modern counterparts.

What was purchased and worn had to be durable enough to endure the work they’d be doing – silk brocade mantua gowns and embroidered coats were not going to cut it! The secondhand clothing found in the markets of the day actually became a great source among the working class for affordable and up-to-date options for dress.

However, this lack of emphasis on fleeting fashion does not diminish its true importance of clothing. “What people wore defined their social position and every colonial government tried with sumptuary legislation to keep class lines clear.” In 1619 in Massachusetts, legislation was passed “against excess apparel” among plain people . The court ordered that offenders be fined by local priests. Nevertheless, the lines blurred in many cases and it became sometimes difficult for guests in well-to-do families’ households to distinguish between the lady of the house and her servant!

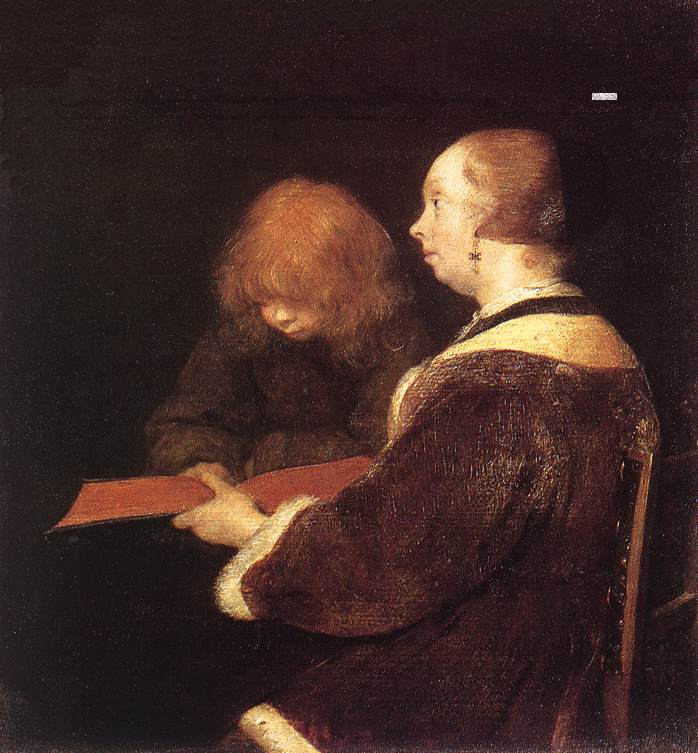

Children of the time followed the same standards as their parents. “Dressed as miniature adults from the time they could walk,” children always knew their families’ status in society and were direct representations of such status. “Wives of the well-to-do imposed standards of proper dress on the children” and likewise, if you were from the country and a farmer’s child, the same aprons, straw hats, and patterns your mother wore would also be your attire.

In the 17th Century, what you wore was much more telling of who you were then in our modern society. In our world, many people can afford even the cheapest imitations of the season’s latest fashions, and children of all families are often dressed up like dolls! But for the Penn Family, their clothing would have reflected their social position and their Quaker beliefs.

Although a man of power and money, William and his family would have dressed in the best fabrics and highest-quality materials, but their religion would have demanded the fashionable embellishment and frills be left off. This was sure to define the family in a rather unique way, in comparison to their Protestant and Anglican English counterparts of equal social rank.

Written by Mary Barbagallo

Further Reading:

Everyday Life in Early America, David Freeman Hawke, Harper and Row, Publishers, Inc. 1988, New York, NY.

The Criers and Hawkers of London: Engraving and Drawings by Marcellus Laroon, Standford University Press, Standford, CA,1990.