In less than 3 weeks, we will have a very exciting event for all members of The Pennsbury Society: a 17th-Century Fashion Show!

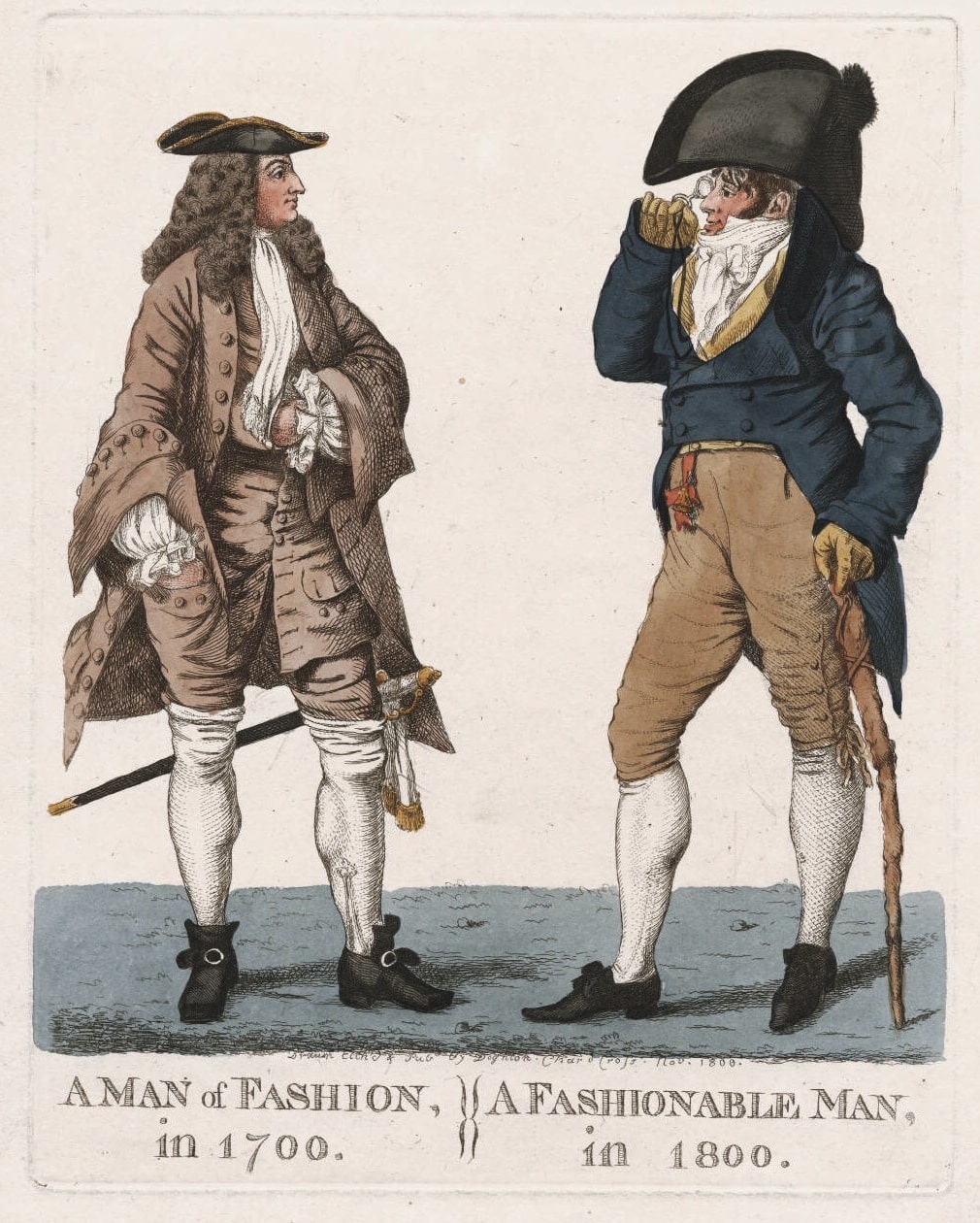

One of the benefits of membership in The Pennsbury Society is access to exclusive programs here at Pennsbury Manor. On Sunday, April 22nd at 2:00pm, our second program of 2012 will take a look at 17th-Century Fashions in England and the Colonies. Staff member and residential costume historian, Hannah Howard, will be sharing all her knowledge on the styles of William Penn’s time, including original artifacts, paintings, and drawings of the era. The program will finish with a Fashion Show of Pennsbury’s clothing collection and discussion of how fashion changed depending on someone’s role in society, with outfits modeled by our very own volunteers!

Pennsbury Manor is a state historic site, but we owe a lot of our program funding to our not-for profit support group, The Pennsbury Society. The funds they raise go to support our educational and specialty programs, including our wonderful Period Clothing Collection! If you haven’t yet become a member of the Pennsbury Society, consider joining and taking advantage of our unique events and opportunities. For more information, please stop by the Visitor Center or see our website: https://www.pennsburymanor.org/support/membership-opportunities/

Those of you that have walked the grounds of Pennsbury may have seen a building called The Worker’s Cottage. This reconstructed outbuilding’s original purpose or even existence is unknown, but we use it to talk about the laboring class’s lifestyle in early colonial Pennsylvania. Most people did not live as luxuriously as William Penn’s family. Most homeowners, or people who worked as an apprentice or slave for a homeowner, lived in a 1-2 room house similar to this.

Those of you that have walked the grounds of Pennsbury may have seen a building called The Worker’s Cottage. This reconstructed outbuilding’s original purpose or even existence is unknown, but we use it to talk about the laboring class’s lifestyle in early colonial Pennsylvania. Most people did not live as luxuriously as William Penn’s family. Most homeowners, or people who worked as an apprentice or slave for a homeowner, lived in a 1-2 room house similar to this.