Pennsbury is pleased to welcome a new addition to our “Living Collections”: meet Romeo!

His next owner was, unfortunately, not responsible in the care for Romeo. In October the staff at Special Equestrians learned that he was to be sent to slaughter. One hero in particular, Kaitlin, rushed over and literally took him off the truck and loaded him into her own trailer for a return to Special Equestrians. Kaitlin found that Romeo had lost 300-400 lbs. and that his ribs were showing. Furthermore, he had rain rot (from not being sheltered properly) and an (thankfully easily treatable) fungal infection that was out of control. Kaitlin nursed him back to health, and special equestrians offered use of a stall. But they could only offer the stall until the beginning of January. Romeo’s future was more uncertain than ever.

Romeo was selected not only for his temperament, but for his looks as well. Arabians are small horses, and our research indicates that many of the horses in early Pennsylvania were under-sized. Romeo is also white and a gelding (castrated male). Records show that William Penn had 2 white mares and a white gelding at Pennsbury Manor.

It is a truly remarkable accomplishment that so many people came together to save a horse, keep Pennsbury’s popular animal program running, and ultimately help our visitors understand the strong link between early settlers and horses. Please stop by this spring (we re-open in March) to meet Romeo and the other residents of Pennsbury’s stables!

Written by Mary Ellyn Kunz, Museum Educator

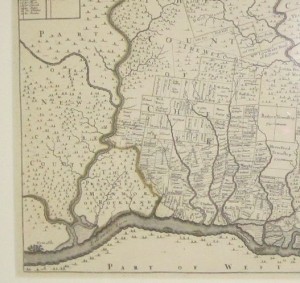

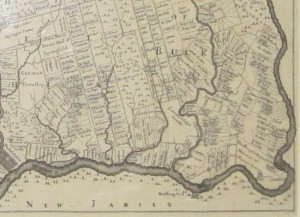

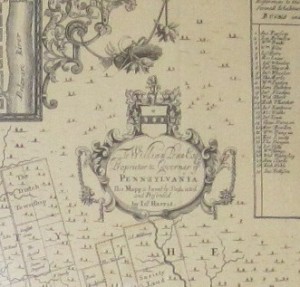

This is, as stated on the artifact, “A MAPP OF YE IMPROVED PENSILVANIA IN AMERICA DIVIDED INTO COUNTIES TOWNSHIPS ANDLOTS. SURVEYED BY THO.HOLMES SOLD BY P.LEA. DEDICATED TO WILLIAM PENNBY INO HARRIS”. This print, shown above, is on display located in the porch of the House, above the fireplace. The map shows Philadelphia and the land along the Delaware River from New Castle to Pennsbury. It is an early 18th century map that is 26 ¼ by 20 ¾ inches in size. It is on white paper done in black printer’s ink and some watercolors.

This is, as stated on the artifact, “A MAPP OF YE IMPROVED PENSILVANIA IN AMERICA DIVIDED INTO COUNTIES TOWNSHIPS ANDLOTS. SURVEYED BY THO.HOLMES SOLD BY P.LEA. DEDICATED TO WILLIAM PENNBY INO HARRIS”. This print, shown above, is on display located in the porch of the House, above the fireplace. The map shows Philadelphia and the land along the Delaware River from New Castle to Pennsbury. It is an early 18th century map that is 26 ¼ by 20 ¾ inches in size. It is on white paper done in black printer’s ink and some watercolors.